Distinguished designer Derek Frost and pioneering entrepreneur and creator of Heaven nightclub, Jeremy Norman, met and fell in love more than 40 years ago. In the early 1980s their friends began to get sick and die. AIDS had arrived in their lives. When the couple got tested, Jeremy received what was then a death sentence – he was HIV positive. Living and Loving in the Age of AIDS is Derek’s moving story of their life together and how they set up the charity Aids Ark helping HIV positive people across the globe. We spoke to Derek about his poignant and informative autobiography recording a devastating era for gay men.

Why did you write your memoir Living and Loving in the Age of AIDS?

Because young people and particularly young queer people need and, I believe, want to know more about what older members of their community experienced during the days of “gay liberation” and the AIDS pandemic.

You travelled widely in your youth, which places made the biggest impact?

I remember Afghanistan with particular affection – the country so big and beautiful and wild… also Afghani men – much the same.

You met your partner, entrepreneur Jeremy Norman, in 1977. Can you tell us about the early years of the Embassy Club and why it was important for gay men?

At that time divisions of type were marked. At the Embassy Club this was not the case. All types went there to dance and play together: upper and lower classes, straights and queers, blacks and whites, celebrities of all sorts, beautiful unknowns, people of every age. One of the Embassy Club’s greatest legacies is how it ignored class and celebrated and welcomed “the other”. It was known as the place “where duchesses dance with rent boys”. For gay men slightly older than us, this was extraordinary. For years, gays had been forced to hide their sexuality in the shadows, scorned by society, considered immoral and criminal. But the Embassy Club changed people’s attitudes to those who are “alternative”. There gays could come out of the shadows and were welcomed by their former detractors. Jeremy must be credited with this.

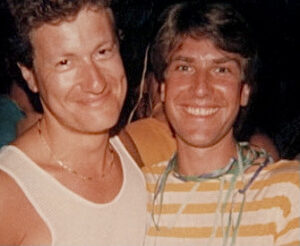

Jeremy Norman and Derek Frost in 1982

Jeremy Norman and Derek Frost in 1982

Can you tell us how Heaven came about and its opening in 1979?

It had always been J’s primary ambition to open a dance club that is only for gay men. It’s daunting to open so large a space to an unknown audience, but J’s courage and intuition was soon rewarded when increasing numbers of enthusiastic gay men and their icons arrived to party there. Madonna, Grace Jones, Boy George, Divine and others demanded to perform to our fast-growing crowd and we were happy when they all did just that. We were “hot” and they knew it was important for their fledgling careers to perform to our gay members. Gay men are trendsetters. The temperature went up and attendance exploded. Thousands came through our doors. Gay men from all over the world heard about Heaven and rushed to visit us, to dance with us, to find each other and to celebrate their unique nature. They felt safe and happy enfolded within its dark embrace. There they can be themselves. Heaven celebrates homosexuality. We extended our invitation to gay women and to all other queer people. Always dancing – us and our tribe. Passion aplenty is there. Love also.

Heaven was sold to Richard Branson quite early. Why was that?

In the summer of 1984, we received an unsolicited and generous offer to purchase Heaven from Richard Branson and his then struggling Virgin Music business. We hadn’t intended to sell the business so soon, but J decided that the number of people willing to buy a gay business of this size might be limited and accepted his offer.

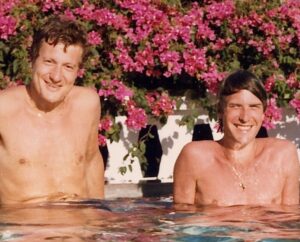

Jeremy and Derek in 1980

Jeremy and Derek in 1980

Jeremy and you have had such a range of businesses: the Embassy Club, Heaven, Pasta Pasta shop, Power Station gym for men, one of the first modern gyms, your design business. Is running businesses in both your DNAs?

It’s certainly in J’s DNA. He leads and I follow – sometimes rather nervously but always confident to be in charge of the design element of any new project.

Can you tell us about Needsore?

There’s an isolated place on the south coast of England that is home to birds and animals of many sorts. Views of water and empty land stretch in every direction. There a tranquil river which snakes through salt marshes and enters the sea at the narrow stretch of water that divides the British mainland from the Isle of Wight. Just to the west of the river, quite alone to the sea side of the salt marshes, stands a long, low red-brick building. Formerly it was home to a coastguard crew, lodged side by side in nine small terraced cottages. The community who live here jokingly call the place Coronation-Street-on-Sea. Its real name is Needsore.

When did you first hear about this new disease that appeared to be targeting and killing gay men?

We first heard about it when we were in Key West, Florida when we read the now famous New York Times article “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” on 3 July 1981.

You visited the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York in those early days in 1985. Can you describe what you saw and the impact it had on you?

My friend and design client, Dorothy Hancock, worked as an AIDS counsellor at Mount Sinai Hospital in NYC. In 1985, I went with her to visit the NYC Drop-In Centre of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, in its third year of operation and already at that point over-subscribed. I was shocked by what I saw there – skeletally thin and sick young men marked by signs of extreme illness. Many had been abandoned by families, friends and even medical people, who feared contagion from the disease. In the shadows of that place, there was a smell of death and despair. “All these young men will die,” Dorothy said. “There is no effective medication.”

In London there was London Lighthouse, it was an important place to you wasn’t it? Can you describe its importance?

In 1986, our friends Andrew Henderson and Christopher Spence opened London Lighthouse: a loving and supportive place to go if you were positive and a beautiful place to die. Many of our friends ended their days there. It was open to all, but most of its service users were young gay men. Its staff of experts and volunteers were infinitely welcoming and loving. No one was judged. There, we saw young men sitting amongst its flower-filled garden looking old, wasted and ill; also the sunlit place, where on generously spaced beds they died. In future years I was to teach regular yoga classes there.

You and Jeremy were also involved in the charity Crusaid?

Jeremy was one of Crusaid’s co-founders and the charity’s first Chairman.

How did Crusaid help people living with AIDS?

We’re all proud of Crusaid’s hardship fund. The deprivation and rejection that individuals with AIDS experience was widespread. The hardship fund was core to our raison d’être. It provided immediate cash for those in urgent need; for those lacking basic necessities, for small luxuries like a trip home to see parents, for a small fridge beside a hospital bed. Most of those it helped were young gay men in their twenties and early thirties. Crusaid also funded HIV/AIDS ward improvements and medical equipment in several hospitals, including the AIDS hospices at both London Lighthouse and the Mildmay Mission Hospital. Over subsequent years, Crusaid raised several million pounds and funded projects both in the UK and overseas.

How were you and Jeremy involved with setting up the Kobler Centre?

Receipt of the Kobler legacy was a great boost to Crusaid’s early development. This, together with NHS funding, was used to open a dedicated HIV/AIDS clinic, the Kobler Centre, at what is now called the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. We were pleased to meet Princess Diana when she opened the centre in September 1988. The Kobler Centre still continues to offer top quality HIV/AIDS outpatient healthcare.

Can you tell us about the moment when Jeremy tested HIV positive and how he and you coped with the news?

We hurried from that doctor trying to get away from him and his ghastly news as quickly as possible. We rushed home barely breathing; went wordlessly and immediately to our bedroom, where we drew the curtains and hid in the dark. Finally alone, we fell into each other’s arms with animal howls which continued without ceasing through that first long night.

Can you tell us more about Pat and the Bristol Cancer Care Centre’s help?

Chris and Pat Pilkington, with whom I once lodged in Bristol, were immediately supportive (of J’s recent HIV+ diagnosis) and introduced us to the techniques they taught at their Bristol Cancer Care Centre. Pat described HIV infection as: “A time bomb waiting in the wings; a strong fear that must be mastered.”

Jeremy was put on AZT as the only available treatment, it must have been a very scary time?

Yes – it was.

So many of your young gay friends were dying, how did you both cope with that amount of death and grief and funerals – alongside Jeremy’s diagnosis?

It didn’t help J’s resolve to survive when we went to endless funerals where we saw so many young people mourning the loss of equally young friends.

AIDS really wrecked your young (and older) friends’ bodies, didn’t it? Can you describe those horrific symptoms and opportunistic infections, as now it seems a world away.

A young person is attacked so thoroughly that his skin gets covered in the dark cancerous scales of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). He loses his sight to Cytomegalovirus (CMV). His brain, attacked by Toxoplasmosis, ceases to function properly. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) fills his lungs with a mucus which prevents him breathing. Neuropathy attacks his peripheral nerves and makes walking too painful. He loses all his body mass due to constant diarrhoea and is reduced to skin and bone. His hair drops out. His youthful appearance is gone. He now looks ancient, shrunken and wizened. He becomes weak. All his energy drains away. And then he dies.

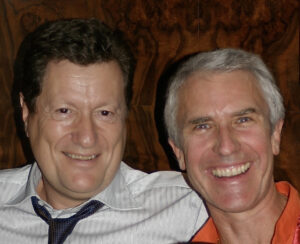

Jeremy and Derek on the night of their civil partnership in 2005 – the first day that UK law allowed same sex unions

Jeremy and Derek on the night of their civil partnership in 2005 – the first day that UK law allowed same sex unions

Yet despite all that was happening you also developed the Soho Athletic Club gym business in Macklin Street? Was that business focus important for Jeremy to survive this period?

We were excited about developing Macklin Street. I was busy drawing up plans. We were going to open a gym on the first floor, maybe a yoga studio on the floor above. At the same time, I worried about the weight of additional responsibility on J. I shared my fears with him at the time and he replied: “I need challenge. Please don’t make me sit in a chair and wait to die. Challenge allows me to get on top of my fear.”

Can you tell us what you and Jeremy felt when you first heard about the successful anti-retroviral drug treatments, trials of which arrived in 1995?

So effective was the triple drug combination that many described taking them as “The Lazarus Effect” – dying people climbed out of their death beds and became healthy again. It was a miracle.

When did Jeremy first go on them?

September 1996.

And then there was triple combination? Can you tell us more about Dr Mike Youle’s role in Jeremy’s care?

Mike became J’s HIV doctor in 1992 – he still is. His role was central to J’s survival. J consulted with Mike on a very regular basis as did all his other many patients. He was and is much loved and admired. Mike is always admirably firm in his views. In November 1994, looking at J’s blood numbers yet again, he told him, “If your CD4 is under 100, you’re in trouble and you need close monitoring. Many more people with CD4 counts of less than 100 are sick and hospitalised compared to those with similar counts who remain healthy. I see many people just like you, healthy but with low CD4 counts. One day they present with an abscess in their head. Within a week they’re dead.” J’s CD4 count at that time was 91.

Derek and Jeremy in 2019

Derek and Jeremy in 2019

Yoga is an important part of your life in this period?

With the threat to J’s health during that period, I also needed to be super-charged healthy, both for myself and for J. Clearly, a disciplined and determined approach was required. I decided to focus on yoga. During my first class, Mary, my teacher, told me that it was as important for me to stay mentally and physically well as it was for J; that my health would be an essential tool in his armoury.

Can you tell us how Aids Ark started?

In January 1995 J suggested starting a charity whose objective would be to raise funds to buy ARVs for positive people in countries where the drugs aren’t free. In the UK, these same drugs are freely available through the NHS. It says a lot about J that he was thinking of others when his own health was so threatened.

How did the Aids Ark name come about?

“The time has come,” J told me in January 2002, “to start our caring initiative in the countries where so many, through lack of access to ARVs, are still dying of AIDS. Let’s call it Aids Ark.” It’s a good name, inspired by the book Schindler’s Ark (and subsequent movie Schindler’s List), as well as a clear reference to Noah’s Ark. Oskar Schindler helped save the lives of over 1,200 Jewish people in Nazi-occupied Poland. “Let’s see if Aids Ark can help do the same for an even greater number of HIV positive people.”

You’ve had so many significant people in your life but can you name three of them who have had a big impact on you?

In 2002, around the time of my 50th birthday, we hosted a party at which I made a short speech: “Three people are here who have made a great impact on my life. I call them the 3 M’s – Mary Fox Linton my design mentor, Mary Stewart my yoga teacher and, most importantly, my Mum.”

Can you tell us about “This Precious Life” with Jeremy?

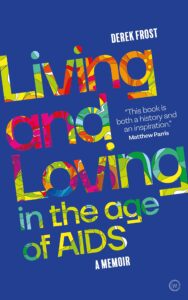

I have. It’s all in my memoir Living and Loving in the Age of AIDS – publishing on 13th April 2021. Preordering is available through Amazon and Penguin Random House and will be much appreciated by my publishers, Watkins Books. Please order my book now. All revenue due to me from sales will be donated to Aids Ark.

Living and Loving in the Age of AIDS by Derek Frost can be pre-ordered from Amazon at https://amzn.to/3anvlYY

Comments

No comments yet, be the first to leave a comment.