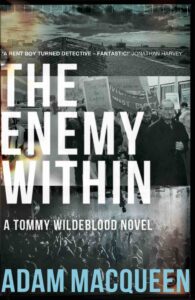

The Enemy Within is Adam Macqueen’s second thriller in his Tommy Wildeblood series. The Piccadilly rent boy turned detective is now studying at the Polytechnic of North London where he falls in love with handsome young Irishman Liam – and gets pulled into radical political activism. We asked Adam Macqueen to tell us more about his new novel which spans the early days of AIDS, filmmaker Derek Jarman, a young Jeremy Corbyn and the bombing of Margaret Thatcher at the Grand Hotel in Brighton.

Why did you set the book in 1984?

It was partly because – and this isn’t really a spoiler because you learn this in the very first scene of the book – the bombing of the Conservative Party Conference in Brighton that year in an attempt to assassinate Margaret Thatcher plays a big part in the plot. But I also wanted to explore the whole world of opposition to Mrs Thatcher at that point – and 1984, at the height of the miners’ strike, was really the last moment (at least until the unexpected promotion of Jeremy Corbyn, who appears in the book as a young MP!) that the whole worldview of the far left seemed like a viable possibility.

You’ve got Ken Livingstone running London, first time around, as a sort of nuclear-free socialist fiefdom which Mrs Thatcher is vindictively trying to shut down, and the Cold War at just about its very coldest that leads to this state of paranoia on both sides, where conspiracy theories and the possibility of real revolution abound. And I also wanted to explore the nature of the gay experience on the left at that point – because retrospectively we seem to have decided that gay rights were always part and parcel of a liberal agenda on the left, and actually before groups like Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) help to force the Labour Party into taking an official position in 1985, that really wasn’t the case: in fact a lot of the most left-wing groups regard equality for homosexuals as a “bourgeois affectation” that’s got nothing to do with the sort of thing they’re fighting for. And the bits of history that we’ve decided to forget, or tidy up neatly after the fact, are always the most interesting bits.

You’ve brought real life gay people from the period into The Enemy Within like Mark Ashton, Derek Jarman and Paud Hegarty from Gay’s The Word. Did you know them personally?

Not one of them! I was nine years old in 1984, and living in the countryside in Somerset, so not yet very plugged in to the gay scene in London. But Derek Jarman became a big part of my life as a teenager, both his films, which I used to watch late at night on Channel 4 when I knew my parents definitely weren’t going to come into the sitting room, and his writing. His death from AIDS was announced on the day I left home in 1994, which of course was also the day of the first vote on equalising the age of consent (which only brought it down from 21 to 18), so that felt like a hugely significant day for me.

Mark and Paud I read up a lot about, because it felt inevitable that in the sort of world I’d put my hero Tommy into, he would run into them. Wherever I can in both the Tommy Wildeblood books so far I’ve included real people where I can, as a kind of tribute I suppose – it doesn’t matter if readers don’t realise they’re actually real people, but if it leads them into finding out more about them, that can only be a good thing. Even the pimps and rent boys who feature in the first book, Beneath The Streets, are based on real-life people interviewed by Jeremy Reed for his excellent non-fiction book The Dilly. Actually, now I’m saying this, I realise it’s probably just laziness. Maybe I just can’t be bothered to make characters up!

I did go in to Gay’s The Word the other week to sign copies of the book, and I was slightly terrified that Jim, the manager who worked alongside Paud, would say “you got EVERYTHING WRONG” – but thankfully, he didn’t, he just said how much he’d enjoyed the book and he was recommending it to other members of LGSM too!

Can you tell us more about your lead character Tommy Wildeblood?

When we first meet Tommy in Beneath The Streets, he’s a rentboy who’s run away from home and been working the meat rack at Piccadilly Circus for four years – but he’s desperate to get out of that line of work, not least because at 20 he thinks he’s too old for it. It leads him into some other work for a private detective that’s actually way more morally questionable – and that’s how he ends up stumbling into the real-life conspiracy to murder Norman Scott, the former boyfriend of the Liberal Party leader Jeremy Thorpe, which is the sort of mad plot I’d never have dared try to come up with as fiction! He turns out – slightly to his surprise – to have a really keen sense of injustice and a habit of putting himself into danger when trying to fight it. By the time we meet him in the new book, he’s moved on and is a mature student at the Polytechnic of North London and living a much less chaotic life – but while he’s tried to forget his past, there are people out there in the shadows who remember exactly what he did eight years ago, and have unfinished business to conclude.

Is Tommy Wildeblood based on someone you knew?

He really isn’t. And he’s not me either, although he carries a lot of the repressed guilt I, and probably every other gay man growing up between the sixties and nineties, dragged out of the closet with us (though he’s dealing with it pretty well, considering!). And there is a point in this book where he has to face the embarrassment of some teenage poetry he wrote coming back to haunt him along with everything else, and that – I’m cringing as I confess this – is actually some genuine Adam Macqueen teenage verse right there. I think I’d be slightly less embarrassed to ‘fess up to sex work than that!

Because my background is in journalism for Private Eye, I tend to have quite a jokey, acerbic writing style. And I was determined at the outset of this not to let Tommy, who’s the first-person narrator of both books, write like I do. So I set myself a rule at page one: no jokes. Only it turned out Tommy actually has a really good sense of humour, and a tendency to take the piss out of himself and everything else. He kept making jokes of his own. Funny that!

And can you tell us a bit more about Irish activist Liam who Tommy falls in love with?

He’s dreamy. But he’s trouble (aren’t they always?). Tommy falls head over heels for him when they meet at a protest against the National Front – and quickly get arrested and thrown in a police cell together. But as their relationship develops, he starts to realise he’s not got the full picture of who Liam actually is, and just how far he might be prepared to go in the name of activism. And being Tommy, this doesn’t scare him off – it just leads him to ask more awkward questions and start sticking his nose into all sorts of areas that he’d be a hell of a lot safer staying out of.

It was fun to write that moment of initial attraction in 1984 terms, too. Tommy’s first impression, before he has a clue whether or not Liam is gay, is of him having “long, dark hair which was nicely looked-after without straying too far into George Michael territory.” Which is one of those times when Tommy, in 1984, is writing something a bit different to what we read in 2022! I had fun with things like that.

You beautifully draw the dating and courting nature of the gay relationship between Tommy and Liam – compared with “Grindr-style” hook ups of today. Was it good to bring more traditional gay romance and sex into the story?

I was sort of surprised when I got to the end of draft one, thinking I’d been writing a thriller complete with car chases and explosions, to discover I’d actually been writing a love story too! But it definitely is. And yes, it was lovely. Tommy starts off pretty world-weary, having, in his own words, “been around the block a bit”, but also finally, at the age of 29, ready for a proper relationship. And he falls hard. Having been with my own husband, the artist Michael Tierney, for 20 years now, it was fun to think my way back into writing those early stages of a relationship, where you’ve got that strange mix of being hugely intimate with someone without actually knowing much about them at all – and you’ve also always got this constant doubt at the back of your mind that it all might go horribly wrong any minute. Which – spoiler alert! – it does pretty spectacularly in Tommy and Liam’s case, but in a manner most readers have almost certainly managed to avoid in their own lives.

The early knowledge about AIDS plays a big part in the story, can you tell us why you included it?

If you’re writing a story about gay men set in the 1980s, it would be pretty impossible to avoid. And it was a fascinating point at which to dip into the story – because this is another thing we’ve slightly tidied up our memories of retrospectively, but 1984 is way before the big government information campaigns and Princess Diana opening dedicated AIDS wards: this is the period before even HIV has been identified as the virus responsible, the Terence Higgins Trust are only just putting out the very first tentative advice, before Rock Hudson’s death catapults it all onto the front pages, and men in the UK are still convinced the “gay plague” might be something they can avoid as long as they don’t have sex with any Americans.

One of your characters Clarrie dies of AIDS. Was she based on a real Soho gay bar owner?

No – Clarrie just came into my head fully formed as a character who I needed to impart some vital information in the first book, and then I fell completely in love with her. I wanted to get some of that already old-school, Polari-era, Quentin Crisp-ish gay Soho into the book, which was set in 1976, and Clarrie, who manages a cellar bar known to everyone as the Up Your Bum and wears full drag at all times, seemed like the right way to do it. And then her role just grew as I started to explore more of Tommy’s past, and the questions of how he’d survived on the streets of London as a teenage runaway, and once Clarrie had become a mentor figure – he says in this book that he’d “got used to thinking of Clarrie as an ever-entertaining, slightly catty aunt, but when I was a teenager she’d been more like a second mother to me” – I had the horrible realisation that I was going to have to kill her. And I hated doing it, and I hope readers hate reading it – they should – but I think when you’re writing about things like the height of the AIDS crisis you have to be as true to life, and indeed death, as you can. To bring in a new and narratively convenient character just to kill them off would have been cheating. The sad fact – and this isn’t something that’s up to me, if this series stays rooted in the real world – is that Clarrie won’t be the first person we and Tommy meet who will die from what at that point was still a definitive death sentence.

You even talk about some real life AIDS doctors in St Mary’s in Paddington at the time. Was it important to represent the people who fought those terrible early battles of HIV and AIDS?

Absolutely. People like Tony Pinching, Ian Weller and Jonathan Weber were, and still are, great heroes.

Can you tell us more about the fight for lesbian and gay rights in the community in the 1980s which you describe so well and the people and organisations you portray?

As I was saying before, it’s really interesting how equal rights for what would now be called LGBT+ people and regarded as an absolutely essential part of any sort of left-wing outlook wasn’t yet part of that package. Talking to activists who were around at the time it was really interesting to learn how the range of attitudes went from determined support in the Socialist Organiser Group, or Soggy Oggies, through to outright hostility in the Militant Tendency and the Worker’s Revolutionary Party, who Tommy and Liam have a very hairy encounter with. And other wild and wonderful groups like the Brixton Faeries, and Icebreakers, who meet at the Gay’s the Word bookshop, which at that point had just been raided by Customs and Excise on the most trumped-up charges you can imagine, out of sheer establishment vindictiveness (the trial collapsed the following year). It was fun to take Tommy and Liam along to one of their meetings, and have Mark Ashton commandeer it to create what will subsequently become LGSM – without the happy couple really noticing, because they’ve only got eyes for each other! I like to think there’s maybe some crossover event going on there where the film Pride is going on at the same time as that bit of my book – two fictionalised versions of reality rubbing up against each other before branching off in slightly different directions.

Ken Livingstone doesn’t appear in the book himself directly but he seemed to be a pivotal figure?

Even as a nine-year-old – from an admittedly lefty, Guardian reading family – I was aware of quite how out there Ken Livingstone was as a politician, with absolutely unembarrassed support for gay rights and all sorts of other things that got written off as being “loony left” stuff but now look absolutely mainstream (even though a lot of them were basic common sense in a diverse city even at the time). Of course this was all before he started going on about Hitler all the time. But back then, and for a long time afterwards, he had the sort of charisma, charm and talent for PR that made him a superstar on the left – he was probably the first of those “politicians who aren’t like other politicians” that people know and have a gut feeling about even if they’re not that engaged with politics. Which, of course, has led us to people like Nigel Farage, Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Which is very depressing!

You also brilliantly represent the left wing activism of the time in terms of support for the miners, Troops Out, Greenham Common and the College of Marxist Education, Icebreakers and so on. Were you actively involved?

Again, not so much aged 9! Although I had gone on a couple of marches with my mum by that point – I remember one, against education cuts in Bristol, where I was allowed to take my toy monkey but I kept stepping on the feet of the man marching in front of us and I was worried he was going to shout at me. And I remember being outraged and furious when my sister told me that she was allowed to go to Greenham Common, but I wouldn’t be. Not that either of us actually did. And now Vladimir Putin has brought back nuclear terror specially to help get people in the mood for my book – isn’t that nice of him!

Without giving too much away, it’s a superb final twist around the bombing of Margaret Thatcher’s hotel in Brighton at the Conservative Party Conference in 1984. What is your memory of that event?

I’m not sure I was aware of it on the night itself. I can imagine I was kept away from the news footage of it all, which having watched again as research for this book, is pretty horrific and scary. But I do remember having a conversation with another boy in my primary school class, who I knew didn’t like Mrs Thatcher the same as me (another set of Guardian-reading parents), and him saying how it was pretty good that some Conservatives had been killed. Which is a very 9-year-old reaction, but actually turned out to be the joke a lot of adults were making at the time. It’s hard to overestimate the level of revulsion there was for the Thatcher government at the time, and vice-versa. All this talk now of everyone becoming polarised and hate-filled by social media – nope. It’s just the medium that’s changed, not the attitudes.

Can you tell us more about yourself and your journalistic and writing career?

It all started with an incredibly lucky break – I applied for work experience at Private Eye in 1997, did a week there producing what I now realise was an alarming number of stories, and then hung around until they finally gave me a job – I used to file stories in between temping placements and working in a café, literally taking print outs into the office and putting them in an in-tray so everyone would remember my face. I left for a bit to work for The Big Issue – I was deputy editor there until I realised I actually wanted to spend my time writing, not telling other people what to write – and Ian Hislop fortunately took me back at the Eye and I’ve been there ever since. I just about overlapped with Ben Summerskill, who later went off to run Stonewall. That always amuses me when people tell me Private Eye is still staffed by deeply homophobic public schoolboys – in 25 years I’ve yet to meet them. One of the earliest recruits to the magazine, who actually features as a character in the first Tommy book, was Tom Driberg, the Labour MP who enjoyed a spectacular and very open gay sex life throughout the 1960s and 70s.

What will your next book The Inalienable Right be about?

We’re moving forward to 1987, and the grotesque and unforgivable attempt to target a group who the government felt weren’t already suffering enough with Section 28, which banned local councils and education authorities from “promoting” homosexuality. Tommy watches a Conservative backbencher on Question Time defending the policy and talking about how “right-minded people don’t want to see their rates going on subsidising sodomy” – and he recognises him as a former client from his Dilly days. So he’s determined to expose him as the hypocrite he is. Which will take him into the world of tabloid journalism at the height of Kelvin Mackenzie’s Sun and Robert Maxwell’s Mirror, and force him to delve back into his own past and revisit some old faces – whose world, like his, has changed forever.

The Enemy Within by Adam Macqueen is published by Lightning Books price £9.99. To order your copy at the special Lesbian & Gay News discount price of £7.99, click here and use the discount code 1984LGN.

Comments

No comments yet, be the first to leave a comment.