The first film I ever saw where a lesbian relationship was depicted openly was Desert Hearts. The film was released in 1986, and by the time I saw it on a grainy portable TV in my bedroom late one night a few years later, I was a young teenager who felt very much more in tune with Jess from Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit than the confident rancher’s daughter Cay in Desert Hearts.

I used to wonder if it was a difference between being American and being English. In America, I thought, perhaps it was much easier to be brightly confident about being a lesbian than it was in the UK. I had dreams about being one of those confident American lesbians, flirting with attractive women and charming them into romance out in the small towns and ranches of the Southwest, rather than being a gawky, awkward English girl who learned very quickly that Mum really didn’t like ‘all that gay stuff’, and so keeping my emerging sexuality quiet.

Of course, my laughable ignorance was, in part, due to the lack of representation in the media. Homosexuality was an exotic curio at best; mostly, it was simply invisible. Like many a closeted lesbian or gay man before me, I was putting together my perspective from a jumble of fragments and not always getting a complete picture.

I learned to find myself echoed in a world that seemed to run on strictly boy-meets-girl rules, watching popular media for the resonating relationships between two people of the same sex, picking up the subtle nods that were like a kind of hidden code to me.

Televised gay kisses made headlines while remaining vanishingly rare, and the few lesbian and gay romances were nearly always shocking subplots doomed to failure or perhaps a bit of spice in a period drama. Maybe that’s why Desert Hearts gave me such a rosy perspective on being a lesbian in America, given that it was a story with a happy ending. You just didn’t see happy, open LGB relationships on screen in the 1980s and 90s.

So, I did what generations of LGB people did before me. I learned to love subtext. I learned to find myself echoed in a world that seemed to run on strictly boy-meets-girl rules, watching popular media for the resonating relationships between two people of the same sex, picking up the subtle nods that were like a kind of hidden code to me. Even when it may well have been entirely unintentional, it mattered.

It spoke to something of the wider LGB experience, too, and having to learn to pick up subtext and cues while you navigated the world as a closeted person, sometimes through the simple nerves that happen to everyone who is trying to find love, sometimes through needing to tread carefully lest you get a jeer or a punch in the face when you came out.

Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit

As I became aware of feelings I had no frame of reference for, I watched the Doctor Who companion, Ace, form a connection with a female alien that ended in tragedy, but which the Doctor assured her would live with her forever. It struck a chord with me that certainly lasted longer than Doctor Who, which ended a few minutes after and wasn’t seen again for another 16 years.

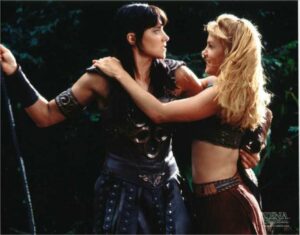

A couple of years later, Xena: Warrior Princess, would occupy my attention due in no small part to her deep, affectionate friendship with her plucky sidekick Gabrielle. Xena had an onscreen heterosexual love interest, but her warm connection with Gabrielle was so iconic it managed to ruffle feathers in the real world, away from ham-acting and Greek legend special effects that couldn’t hold a candle to Ray Harryhausen’s some 30 years before. The relationship always remained subtext, with the writers and the network keen to retain distance from an open lesbian relationship, but there were still plenty of hints and nudges within the dialogue and storylines.

Later still, I would see these subtextual hints in the relationship between the resurrected Ellen Ripley and Winona Ryder’s android Call in the otherwise disappointing sequel Alien Resurrection.

There were, of course, films which took source material that was much more openly lesbian in character and shunted the relationships mostly back into subtext, like Fried Green Tomatoes or The Color Purple, and I’m glad that such a thing would be unlikely today, mostly because it’s dishonest. It took a sustained effort to bring lesbian and gay men out of the mocking or pitiable token or the complete subtext, and characters in fictional drama are only one aspect of what representation means for us. However, as we’ve moved on from tokenism or silence, I’ve noticed something else happening, and I don’t think it’s a positive development.

Xena: Warrior Princess

You won’t miss a lesbian or gay relationship onscreen these days. You won’t miss it because it may often be done with such leaden, unsubtle skill as to make you forget that LGB people have been successfully involved in the entertainment industry since the year dot.

LGBT+ online publications and clickbait sites will devote pages of breathless excitement to analysing the output of streaming services and soaps keen to capitalize on the current commercial cache associated with Pride and the burgeoning rainbow market. Sometimes they pick apart openly LGB character plotlines, or even more breathlessly describe the specific identity from the rest of the alphabet acronym that a character has in place of an interesting storyline. I’ve seen more than one of these dramas done with all the subtlety of a didactic Christian film that desperately wants you to convert by the end of the movie.

That’s not to say all modern lesbian and gay onscreen relationships are badly done, of course. Gentleman Jack was a gloriously layered period romance about Anne Lister, ‘the first modern lesbian’. Russell T Davies, no stranger to bringing the stories of gay men to vibrant onscreen life, recently gave us It’s a Sin, which was good because Davies is a talented writer. However, he’s just thrown a barb at the Disney+ Marvel show Loki for a casual onscreen comment indicating that Loki is bisexual, calling it a ‘feeble gesture’ and I don’t think he’s wrong.

You won’t miss a lesbian or gay relationship onscreen these days. You won’t miss it because it may often be done with such leaden, unsubtle skill as to make you forget that LGB people have been successfully involved in the entertainment industry since the year dot.

In amongst authentically powerful programmes in the tradition of Tipping the Velvet or Queer as Folk, we have an industry often so beholden to checkbox ‘representation’ that it has overlooked the need to tell real stories. It’s all very well for Loki to be acknowledged as bisexual, but what does it add to the show except to generate those breathlessly thrilled Digital Spy clickbait articles?

As lesbian and gay visibility has increased a strange thing has happened to subtext. It’s started to be dismissed as ‘queerbaiting’. This relatively recent term seems to acknowledge that homosexual relationships have become a commodity that can be marketed, but most uses of it are not critiquing this commodification, they are simply complaining that the target of the exploitation wasn’t explicit enough.

Killing Eve was recently monstered for the portrayal of the relationship between Eve and Villanelle, a connection that was intense, twisted, and to my lesbian eyes (which remembered the heady excitement of seeing a part alien Ellen Ripley and her android would-be murderer Annalee Call looking curiously at one another), thick with all kinds of subtext.

The spark between Villanelle and Eve might be lesbian, it might be something else. There’s a case to be made either way. But what on earth is going on when people are both demanding representation so ubiquitous that they want to see an LGBTQIA+ character in everything from CBeebies to EastEnders, to an adaptation of Jane Eyre, but also having a tantrum if anything has a possible homosexual subtext that doesn’t follow prescribed rules?

It’s a Sin

It’s as though there is a tug of war going on between those who merely want the stories of lesbian, gay and bisexual relationships to join heterosexual and indeed, platonic relationships as tales that we enjoy and connect with, and those who seem to have a desperate need for everything to be signposted and underlined in sharpie so that no one could possibly miss the inclusion and diversity messaging.

Personally, I rejoice that television and film can now tell lesbian and gay stories openly, and that it no longer generates newspaper headlines when two homosexual men or women are depicted chastely kissing one another. But I confess I do miss the ambiguity of subtext that seemed obvious once you saw it but may well be missed by the heterosexual people who had a very different perspective.

Subtext is simply part of the way we tell stories, and it should be no different for same sex relationships.

These layers are still permitted in depictions of heterosexual relationships. The ‘will they, won’t they?’ theme is allowed to thrum excitedly below the surface in everything from Marvel movies to television detective dramas like the Strike adaptations. Showing heterosexual relationships openly is the norm, but it doesn’t make subtextual layers between men and women some unacceptable and cynical tease. Subtext is simply part of the way we tell stories, and it should be no different for same sex relationships.

In moving away from tokenism or silence, I worry that we are in danger of portraying LGB relationships and stories as bland, one note placards, instead of the rich and truly diverse lives that homosexual and bisexual people have campaigned long and hard to enjoy. I want young and old LGB people alike to see themselves portrayed openly in film and on TV, but I don’t think that, because of shrill Q-slur slogans and paint-by-numbers representation, any of us are served by the end of subtext.

Kay Knight is a British writer and podcaster. She has a particular focus on women’s stories, and an enduring fondness for Doctor Who, despite everything.

Using the much-celebrated "Brokeback Mountain" as an example, I can list everything I dislike about Gay portrayals on screen: 1) romantic leads with zero chemistry, 2) poorly-lit love scenes or 3) Gay sex and intimacy played for shock value 4) overwrought acting that lacks even a pinch of subtlety 4) narratives that throw a pity party for the "tragedy" of being Gay. I was so outraged at "Brokeback", I nearly walked out. I would have, too, if the ticket hadn't been complimentary! As for TV, I have no desire to see any of these portrayals trumpeted as "queer visibility" in what passes for the Gay press nowadays. It's gotten to the point where I'd much rather read about Gay relationships than see them depicted.