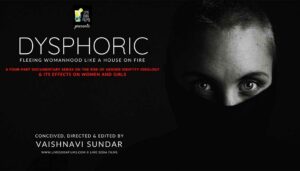

Cancel culture is contagious. Spreading from the US and across Europe, it seems the latest to be infected are the university educated elite of India. As elsewhere, those who speak out for women’s sex-based rights are routinely smeared, threatened and forced out of jobs. One of India’s first victims is Vaishnavi Sundar, a feminist film-maker and activist based in Chennai. Jo Bartosch spoke to Vaishnavi about her latest documentary Dysphoric.

Five years ago, Vaishnavi achieved a significant win for women in her state when she successfully campaigned for the contraceptive pill to be made available. Today, those who once proudly supported her activism have turned their backs on her. Not only has Vaishnavi faced ostracization within mainstream ‘progressive’ and conservative communities in India, she has also been no-platformed from film festivals across the globe. This is because she is the wrong sort of feminist; she has been branded a ‘terf.’ This experience of being ‘cancelled’ made Vaishnavi more determined to raise awareness about the harms of uncritical acceptance of gender ideology.

Born into a conservative, religious family Vaishnavi rages against the social and legal codes that restrict the freedoms of women and girls in India. I spoke with her about her most recent film, Dysphoric: Fleeing Womanhood Like a House on Fire and life as a feminist campaigner in India.

Vaishnavi is angry about the deeply rooted inequality in what is so frequently referred to as ‘the world’s largest democracy.’ She tells me:

“In India porn is endemic, sexual harassment in public spaces is totally normal and at home the Indian Penal Code allows a man to rape his adult wife. There are many reasons why women might want to escape womanhood, but nobody really has the time to care for a woman’s physical well-being let alone her mental well-being.”

Dysphoric is controversial; a four-part hard-hitting documentary it follows the rise of gender dysphoria in young people across the UK and US. Speaking directly to camera, the film captures the experiences of women who have suffered from or treated the condition. Crucially, Dysphoric includes interviews with a growing community who have stopped or attempted to reverse their transition, so-called desisters and detransitioners.

“The notion that a woman can actually have a physical relationship with another woman is incomprehensible even in 2021. And because gay marriage has not been legalized the only way for women to be in lesbian relationships with the person they love is to transition.”

The film opens with Vaishnavi sharing her memories of recognising inequality in her own home and community, of the policing of her behaviour and interests. A series of dreamlike cartoons guide the viewer through her experience of gender dysphoria as a girl. She tells me:

“I wanted some part of India in the film and there is no better way to do it than put myself in the film. I hope that by sharing my history other women might be able to understand their own feelings of discomfort in their bodies. And I wanted to show how all the things that are already happening in the US and UK will happen here in a matter of five to six years.”

Vaishnavi explains that in India whilst homosexuality is technically legal it is socially unacceptable. She believes that this, along with the influence of well-funded international NGOs and domestic woke campaigners, has led to a dramatic rise in the numbers of people identifying as transgender.

“India is an extremely homophobic country. The welcoming of transgender ideology has to be looked at from multiple vantage points. On the one hand there are liberal organisations that genuinely think that we need to provide marginalised people with a voice. And then there is this other section that is promoting transgender ideology as a way of conversion therapy.

“For example, in parts of India it is shameful to be an effeminate man; there is a cultural overlap dating back to the eunuchs of the Mughal Empire. Still today we have the hijra, men who are trafficked or sold into prostitution as little boys and castrated. Some now identify as trans, recognising there’s some money to made from it, though most are angry at the imposition of a Western category. For people who have no clue what’s going on in India, to call boys who sometimes bleed to death during castration, ‘trans’ does disservice to those who are physically and sexually abused in prostitution.”

Vaishnavi hints the imposition of ‘trans’ identities on hijra could be the subject of a film in the future, but Dysphoric focuses on the experiences of women and girls. The documentary explores the growth in the numbers of girls seeking to transition. Many leading psychiatrists, including those interviewed by Vaishnavi, believe that children who might grow up to be same sex attracted as adults are at risk of being diagnosed as transgender. Their concern, which is shared by feminists like Vaishnavi, is that the administration of puberty blockers and cross sex hormones is a form of conversion therapy; one that particularly impacts upon young lesbians.

Vaishnavi tells me:

“The notion that a woman can actually have a physical relationship with another woman is incomprehensible even in 2021. And because gay marriage has not been legalized the only way for women to be in lesbian relationships with the person they love is to transition.”

Vashnavi began to think about making the film following her experience of being cancelled.

“My film But What Was She Wearing? was India’s first feature-length documentary on workplace sexual harassment. I was in the US for an exchange programme, and I wanted to use the opportunity to screen my film at various places while I toured the country. One screening was scheduled in New York. A week before the screening, the organiser sent me an email informing me the event would be cancelled because of my ‘transphobic’ views. Overnight I had become a hate-figure; what surprised and intrigued me was that it was women doing it.”

There is a caste dimension to sexual politics in India. Poor women, particularly those in rural areas, do not have access to the most basic amenities. Lower caste women, most of whom are illiterate, risk rape because they are forced to defecate outside due to a lack of single sex facilities. Rather than secure the most basic rights and protections, India’s educated elite have become embroiled in woke, trans activism.

Vaishnavi Sundar

Indian social media is awash with upper-middle class young people ‘coming out’ as queer in posts which are lauded as ‘brave’ by their similarly heterosexual-yet-special peers. To Vaishnavi, this is a way to stand out from what is always a crowd in the densely populated country. As in the rest of the world, trendy brands are cashing-in on the mania for all things glitter and rainbow to parade their woke credentials. Vaishnavi believes, particularly in the arts, that being ‘queer’ is a way to guarantee attention and kudos.

“The women who want to transition are lied to. They are led to think it’s going to be a little painful for a while, but that transition will solve their problems. After expensive medical treatment they realise the problem is not solved. So in the film we talk about the damage; how puberty blockers and cross sex hormones can increase the risk of heart, kidney and liver diseases. But I also wanted to talk about what happens when you quit testosterone too. I wanted to focus on that because you can’t just watch a film and then say, ‘okay I’m stopping it’, you need help to stop it.”

Mainstream social justice movements in India are bound-up with the politics of Western gender identity and pro-sex work movements. A case-in-point is MamaCash, an international grant-making body which claims to “support women, girls and trans people and intersex people who fight for their rights.” In 2018 MamaCash donated to ‘sex work’ groups, led-by male trans activists, to stop the passage of anti-trafficking bills in the Indian parliament. MamaCash is just one of thousands of organisations supporting similar pro-sex work and pro-transgender organisations across the world. Feminists like Vaishnavi have been left with nowhere inside India to turn for support, and the women and children trafficked into the sex industry are the collateral damage of clueless woke initiatives.

As elsewhere, in India challenge to the dominant ‘born in the wrong body’ narrative is not welcomed, so Vaishnavi was careful to remain balanced when making the film.

“I have been very clear in the film so that no-one can accuse me of transphobia. I’m essentially offering information that should be provided. Through my research I realised that YouTube and social media are full of positive stories about taking hormones and having surgery, but nothing about the ill effects or lifelong damages.”

Since the passing of Transgender Protection Act two years ago hospitals have begun to offer free ‘gender confirmation’ surgeries. Vaishnavi has hit the brick wall of government bureaucracy and her requests for information on the numbers of procedures and follow-up treatments have been stymied. Across popular YouTube channels in India private endocrinologists and surgeons make unevidenced claims and promises, luring in young patients.

“The women who want to transition are lied to. They are led to think it’s going to be a little painful for a while, but that transition will solve their problems. After expensive medical treatment they realise the problem is not solved. So in the film we talk about the damage; how puberty blockers and cross sex hormones can increase the risk of heart, kidney and liver diseases. But I also wanted to talk about what happens when you quit testosterone too. I wanted to focus on that because you can’t just watch a film and then say, ‘okay I’m stopping it’, you need help to stop it.”

Across the world, detransitioners, free speech advocates and radical feminist communities have celebrated Dysphoric as an exceptional piece, dealing with a politically volatile subject with compassion and rigour. But those who Vaishnavi was hoping to convince simply refuse to watch it. She tells me with obvious frustration:

“There is resistance to even the suggestion of watching the film. Those who believe I’m transphobic dismiss the film as transphobic. But I have a feeling that if they give it a shot even if they ‘hate watch’ it, maybe there is some scope for conversation there. I mean it’s free on YouTube, I can’t make it any more available to them.”

One hopes that there remain a few free-thinking legislators with the time to watch Vaishnavi’s documentary. Had she slapped a rainbow on her documentary and called herself queer, Dysphoric would be shown at festivals around the world and afforded well-deserved plaudits. What Vaishnavi has done is brave, Dysphoric is powerful and timely. In the US and UK the fight to protect children and young people has begun, in India Vaishnavi is it.

Dysphoric can be watched for free here.

I'm looking forward to watching this. Her work is so important.

Just the sort of film for LGNTQ etc film festival but I am sure the BFI would not have the balls to show it. Shows how “real” women suffer in India.